Spinal injuries

by Francois Tudor

Patients with spinal injuries should be immobilised and have their spines imaged. Immobilisation includes cervial spine hard collar with blocks, spinal board and log rolling. This MUST be continued until the spine has been cleared or stabilised.

Often both CT and MRI are required to determine the extent of complex injuries of the spine. The images should be reviewed by spinal or neuro surgeons to determine the best management plan for the patient.

Fractures

Cervical spine injuries carry risk of spinal cord injury, so the first priority is immobilisation using a hard collar and blocks as per the ATLS protocol. Investigation is with CT to gain information on the extent of bony injury and MRI for information on spinal cord and ligament injury. Displaced cervical spine fractures and dislocations require reduction and, depending on stability, may require surgical stabilisation (especially if ligamentous

disruption), fusion or immobilisation with specialised collars or braces.

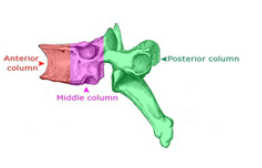

Thoracic and lumbar spine fractures are investigated in a similar manner. Anatomically, the spine is divided from front to back into thirds, representing the anterior, middle and posterior columns. Compression fractures (often seen in osteoporosis) involve the anterior column and usually require a brace for 12 weeks. Burst fractures may involve all 3 columns and usually are managed in a brace for a similar period. However, a kyphosis

deformity, neurological deficit, spinal canal compromise of > 50% or > 50% loss of anterior column height are indications for surgical stabilisation. Other injury patterns including fracture-dislocations and flexion-distraction injuries are routinely treated with surgical stabilisation.

Often both CT and MRI are required to determine the extent of complex injuries of the spine. The images should be reviewed by spinal or neuro surgeons to determine the best management plan for the patient.

Fractures

Cervical spine injuries carry risk of spinal cord injury, so the first priority is immobilisation using a hard collar and blocks as per the ATLS protocol. Investigation is with CT to gain information on the extent of bony injury and MRI for information on spinal cord and ligament injury. Displaced cervical spine fractures and dislocations require reduction and, depending on stability, may require surgical stabilisation (especially if ligamentous

disruption), fusion or immobilisation with specialised collars or braces.

Thoracic and lumbar spine fractures are investigated in a similar manner. Anatomically, the spine is divided from front to back into thirds, representing the anterior, middle and posterior columns. Compression fractures (often seen in osteoporosis) involve the anterior column and usually require a brace for 12 weeks. Burst fractures may involve all 3 columns and usually are managed in a brace for a similar period. However, a kyphosis

deformity, neurological deficit, spinal canal compromise of > 50% or > 50% loss of anterior column height are indications for surgical stabilisation. Other injury patterns including fracture-dislocations and flexion-distraction injuries are routinely treated with surgical stabilisation.

Traumatic cord injury

Injury to the spinal cord may be complete or incomplete and usually occurs in young males involved in motor vehicle accidents, falls and sports related injuries. Initially spinal shock results in a 24-72 hour period of paralysis, hypotonia and areflexia. When it resolves, spasticity, hyperreflexia and clonus progress and only after full resolution can the level of injury be determined. The functional level is determined by the most distal intact

functioning dermatome and motor level (with a minimum of ‘fair’ motor power).

Cord injury occurs due to contusion and compression with resultant ischaemia at the time of a fracture or dislocation of the spine. Incomplete lesions include the central and anterior cord syndromes, Brown-Sequard syndrome and single nerve-root lesions.

Most cord injured patients require treatment in a specialist centre in an ITU setting for the first weeks to overcome the life-threatening medical conditions associated with cord injury. Surgical treatment is required to reduce dislocations and decompression may be indicated

for incomplete lesions with persistent compression, which may lead to an improvement in level. Spinal fusion may be utilised to speed rehabilitation and prevent progressive deformity at the fracture level.

Rehabilitation is dependent on the level of cord injury and requires input from a multidisciplinary team including physicians, surgeons, physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Injury to the spinal cord may be complete or incomplete and usually occurs in young males involved in motor vehicle accidents, falls and sports related injuries. Initially spinal shock results in a 24-72 hour period of paralysis, hypotonia and areflexia. When it resolves, spasticity, hyperreflexia and clonus progress and only after full resolution can the level of injury be determined. The functional level is determined by the most distal intact

functioning dermatome and motor level (with a minimum of ‘fair’ motor power).

Cord injury occurs due to contusion and compression with resultant ischaemia at the time of a fracture or dislocation of the spine. Incomplete lesions include the central and anterior cord syndromes, Brown-Sequard syndrome and single nerve-root lesions.

Most cord injured patients require treatment in a specialist centre in an ITU setting for the first weeks to overcome the life-threatening medical conditions associated with cord injury. Surgical treatment is required to reduce dislocations and decompression may be indicated

for incomplete lesions with persistent compression, which may lead to an improvement in level. Spinal fusion may be utilised to speed rehabilitation and prevent progressive deformity at the fracture level.

Rehabilitation is dependent on the level of cord injury and requires input from a multidisciplinary team including physicians, surgeons, physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Assessment and management of spine trauma

by James Donaldson

Scenario: called to A&E to assess a 19 year old man who was involved in a high speed RTA.

History:

Age, occupation, mechanism of injury, energy, condition of patient / others, air bags, state of vehicles involved

Time/date of injury. Last ate or drunk

Past medical/surgical history. Co-morbidities

Medication/drugs and allergies

Presume a spinal injury until proven otherwise, both Clinically and radiographically

Lateral C-spine is part of the trauma series. AP and odontoid can be used in addition

History:

Age, occupation, mechanism of injury, energy, condition of patient / others, air bags, state of vehicles involved

Time/date of injury. Last ate or drunk

Past medical/surgical history. Co-morbidities

Medication/drugs and allergies

Presume a spinal injury until proven otherwise, both Clinically and radiographically

Lateral C-spine is part of the trauma series. AP and odontoid can be used in addition

- But high false negative rate

- Get CT scan if there is any concern

Cervical spine

Physical examination:

- log roll and assess entire spine: bruising, tenderness, step, deformity

- neurological exam

Clinical clearance possible ONLY if:

Radiographic clearance:

- Primary survey: airway and C-spine control, breathing, circulation, disability, full exposure

- Secondary survey

- Spine:

- log roll and assess entire spine: bruising, tenderness, step, deformity

- neurological exam

Clinical clearance possible ONLY if:

- Awake, alert and not intoxicated

- No neck pain, tenderness

- No neurology

- No distracting injury

Radiographic clearance:

- AP, lat and open mouth peg view

- Must include top of T1 vertebrae

- 15% false negative and CT has largely replaced X-ray in most trauma centres

- CT alone can be used to clear the spine in an unconscious patient

|

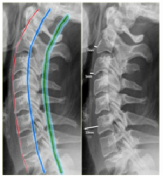

Radiographic assessment:

- at C3 and C4 no more than 5 mm. - at C6 it is wider due to esophagus and cricopharyngeal muscle, but should not exceed 22 mm in adults or 14 mm in children younger than 15 years. |

Thoracolumbar spine

Vertebral compression fractures

- >20 degrees angulation

- multiple adjacent #s

- failure of >2 of 3 columns

- Commonest fragility # (osteoporosis). Usually low energy injury.

- Only 25% of patients seek medical attention

- Examine for focal tenderness

- Spinal cord injury very rare

- Manage symptoms. Normally stable. Analgesia and mobilise

- In first presentation, perform metabolic screening (for osteoporosis) and investigate for infection and multiple myeloma (inflammatory markers, urine Bence Jones proteins). Refer as necessary

- Kyphoplasty (create a cavity and inject cement) if severe pain persists after 6 weeks

- Unstable if:

- >20 degrees angulation

- multiple adjacent #s

- failure of >2 of 3 columns

- Spinal precautions if concern and admit for CT scan

Burst fractures

- Vertebral fracture with anterior and middle column involvement

- Usually high energy injury

- Can be unstable. Admit with spine precautions

- Inform senior

- CT necessary to define anatomy of injury. MRI may be necessary if neurological defecit

- Spinal opinion recommended. Discuss urgently if neurology present or develops

Chance fracture

-

Flexion-distraction injury - high energy injury

- Anterior column fails under compression

- Middle and posterior columns fail under tension

- CT and MRI needed. Admit. Spinal precautions. Discuss with senior and spinal surgery

- Discuss urgently if neurology present or develops

- TLSO (thoracolumbar support orthosis) brace or surgical stabilisation

Fracture-dislocation

- Very high energy injury

- Discuss urgently with senior and specialist spinal centre

- Surgical reduction and fixation necessary