Other joint disorders

There are a number of common disorders of the joints that do not fit clearly into the categories on this website. They are discussed in here to cover the pathology that is regularly seen in musculoskeletal clinics.

Shoulder problems

Subacromial impingement

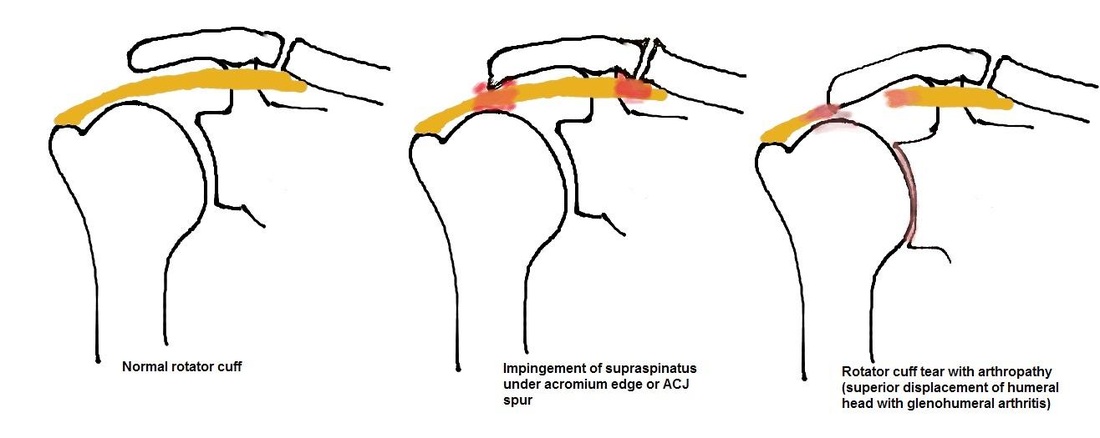

The tendon of supraspinatis, one of the rotator cuff muscles, runs under the acromion and the acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) and functions to abduct the shoulder. The tendon is protected from the undersurface of the acromion by a bursa that allows it to glide smoothly in this tight space. Anatomical abnormality in the shape of the acromion or degeneration with formation of spurs on the underside of the ACJ can lead to the tendon rubbing painfully against these structures, leading to inflammation within the bursa and tendon and possibly to eventual tendon damage and rupture. Young patients presenting with impingement must have shoulder instability ruled out as a cause of their impingement.

The patient presents with pain upon initiating abduction and worsening with overhead movements. The impingement test will be positive with limited abduction of the shoulder. X-rays may show a downward sloping acromion or ACJ spurring. MRI shows inflammation within the tendon and bursa and will determine if there is overt damage to the tendon.

Treatment is with analgesia and physiotherapy. Steroid injections into the subacromial bursa may help relieve symptoms enough for physiotherapy to progress. Continued painful symptoms despite these conservative measures may be treated with arthroscopic subacromial decompression in which the undersurface of the acromion and ACJ are shaved and the inflamed bursa excised. After this procedure, symptoms may take up to 3

months to resolve.

The tendon of supraspinatis, one of the rotator cuff muscles, runs under the acromion and the acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) and functions to abduct the shoulder. The tendon is protected from the undersurface of the acromion by a bursa that allows it to glide smoothly in this tight space. Anatomical abnormality in the shape of the acromion or degeneration with formation of spurs on the underside of the ACJ can lead to the tendon rubbing painfully against these structures, leading to inflammation within the bursa and tendon and possibly to eventual tendon damage and rupture. Young patients presenting with impingement must have shoulder instability ruled out as a cause of their impingement.

The patient presents with pain upon initiating abduction and worsening with overhead movements. The impingement test will be positive with limited abduction of the shoulder. X-rays may show a downward sloping acromion or ACJ spurring. MRI shows inflammation within the tendon and bursa and will determine if there is overt damage to the tendon.

Treatment is with analgesia and physiotherapy. Steroid injections into the subacromial bursa may help relieve symptoms enough for physiotherapy to progress. Continued painful symptoms despite these conservative measures may be treated with arthroscopic subacromial decompression in which the undersurface of the acromion and ACJ are shaved and the inflamed bursa excised. After this procedure, symptoms may take up to 3

months to resolve.

Rotator cuff tear

There are 2 major causes of rotator cuff tears: failure due to repetitive stresses seen in young athletes (rare and treated with physiotherapy) and degeneration thought to occur due to continued subacromial impingement, with a partial tear progressing to a fullthickness tear and eventually rotator cuff arthropathy (secondary arthritis of the shoulder joint) in elderly patients. A third of people over the age of 60 will have some degree of

rotator cuff tear, some more symptomatic than others.

Patients describe an insidious onset of pain and weakness with pain worsened with overhead movements. Examination will reveal reduced range of motion and weakness on testing of the specific rotator cuff muscles. X-rays may be normal but chronic disease may show superior migration of the humeral head (due to the unresisted pull of deltoid) or evidence of glenohumeral arthritis.

Treatment depends on the presentation. Chronic cuff tears are treated initially with analgesia and physiotherapy with an aggressive rotator cuff strengthening programme, possibly with subacromial steroid injections to help control pain. Chronic, symptomatic tears that have had a full rehabilitation programme may benefit from surgical repair. Acute rotator cuff tears should have an early surgical repair. Repair is either open or arthroscopic and relies on suture anchors to reattach the rotator tendons to their normal position. This is usually combined with subacromial decompression. Following surgery, immobilisation and rehabilitation follows a protracted course of around 6-9 months but results are generally

very good.

There are 2 major causes of rotator cuff tears: failure due to repetitive stresses seen in young athletes (rare and treated with physiotherapy) and degeneration thought to occur due to continued subacromial impingement, with a partial tear progressing to a fullthickness tear and eventually rotator cuff arthropathy (secondary arthritis of the shoulder joint) in elderly patients. A third of people over the age of 60 will have some degree of

rotator cuff tear, some more symptomatic than others.

Patients describe an insidious onset of pain and weakness with pain worsened with overhead movements. Examination will reveal reduced range of motion and weakness on testing of the specific rotator cuff muscles. X-rays may be normal but chronic disease may show superior migration of the humeral head (due to the unresisted pull of deltoid) or evidence of glenohumeral arthritis.

Treatment depends on the presentation. Chronic cuff tears are treated initially with analgesia and physiotherapy with an aggressive rotator cuff strengthening programme, possibly with subacromial steroid injections to help control pain. Chronic, symptomatic tears that have had a full rehabilitation programme may benefit from surgical repair. Acute rotator cuff tears should have an early surgical repair. Repair is either open or arthroscopic and relies on suture anchors to reattach the rotator tendons to their normal position. This is usually combined with subacromial decompression. Following surgery, immobilisation and rehabilitation follows a protracted course of around 6-9 months but results are generally

very good.

Shoulder dislocation (also covered in trauma)

The shoulder has an extensive range of motion, relying predominantly on soft tissue structures and the rotator cuff muscles for stability. Because of this, it is at risk of becoming unstable and is the most frequently dislocated joint in the human body. The most common direction of dislocation is anterior (95%), usually occurring with a sudden force applied to an abducted, externally rotated arm. Posterior dislocation is rare and easy to miss,

sometimes occurring due to epileptic seizure, electroconvulsive therapy or electrocution.

Treatment requires urgent reduction utilising analgesia and sedation with various traction manoeuvres described. Assessment of axillary nerve function (sensation in the regimental badge region – known as the stars and stripes area in the US - and deltoid motor function) must be performed before and after reduction as this nerve may be damaged during dislocation or reduction. The shoulder is immobilised in a sling (with some controversy regarding a sling in external rotation versus internal rotation), followed by physiotherapy led rotator cuff strengthening exercises.

A dislocation will damage the soft tissues and capsule that are so vital to the stability of the shoulder joint. Repeated dislocations may also lead to injury to the bony structures of the glenoid and humeral head, making reduction and subsequent stability more difficult to achieve. The younger the age of first dislocation, the higher the risk of subsequent dislocations. Multiple dislocations, particularly in young patients, may warrant surgical

stabilisation to prevent recurrence and this may be performed as open or arthroscopic surgery. If there is bony involvement, this needs to be dealt with at the time of surgery or the resulting stability may be compromised.

The shoulder has an extensive range of motion, relying predominantly on soft tissue structures and the rotator cuff muscles for stability. Because of this, it is at risk of becoming unstable and is the most frequently dislocated joint in the human body. The most common direction of dislocation is anterior (95%), usually occurring with a sudden force applied to an abducted, externally rotated arm. Posterior dislocation is rare and easy to miss,

sometimes occurring due to epileptic seizure, electroconvulsive therapy or electrocution.

Treatment requires urgent reduction utilising analgesia and sedation with various traction manoeuvres described. Assessment of axillary nerve function (sensation in the regimental badge region – known as the stars and stripes area in the US - and deltoid motor function) must be performed before and after reduction as this nerve may be damaged during dislocation or reduction. The shoulder is immobilised in a sling (with some controversy regarding a sling in external rotation versus internal rotation), followed by physiotherapy led rotator cuff strengthening exercises.

A dislocation will damage the soft tissues and capsule that are so vital to the stability of the shoulder joint. Repeated dislocations may also lead to injury to the bony structures of the glenoid and humeral head, making reduction and subsequent stability more difficult to achieve. The younger the age of first dislocation, the higher the risk of subsequent dislocations. Multiple dislocations, particularly in young patients, may warrant surgical

stabilisation to prevent recurrence and this may be performed as open or arthroscopic surgery. If there is bony involvement, this needs to be dealt with at the time of surgery or the resulting stability may be compromised.

Other upper limb problems

Tennis elbow

Repetitive rotation with the forearm in extension may result in a micro-tear of the common extensor origin at the elbow (lateral epicondyle) with a deranged healing response, leading to a chronic inflammatory response. This leads to pain and localised tenderness, worsened with resisted wrist extension.

Initial treatment involves activity modification, compression braces, stretching exercises and ultrasonic massage, and NSAIDs. Localised steroid injections combined with these other conservative measures may be beneficial in up to 95% of cases. Unremitting symptoms may require open surgical debridement.

Tennis elbow

Repetitive rotation with the forearm in extension may result in a micro-tear of the common extensor origin at the elbow (lateral epicondyle) with a deranged healing response, leading to a chronic inflammatory response. This leads to pain and localised tenderness, worsened with resisted wrist extension.

Initial treatment involves activity modification, compression braces, stretching exercises and ultrasonic massage, and NSAIDs. Localised steroid injections combined with these other conservative measures may be beneficial in up to 95% of cases. Unremitting symptoms may require open surgical debridement.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Median nerve compression in the carpal tunnel is the most common entrapment neuropathy in the upper limb, causing pain and numbness in the distribution of the nerve. The carpal tunnel has 3 sides which are rigid bony structures, its floor being the proximal carpal row, with the side walls of the scaphoid and trapezium radially and the pisiform and hook of hamate ulnarly. The roof is made of the transverse carpal ligament, another rigid

structure. Through this tunnel runs the median nerve, accompanied by 9 flexor tendons. Any change in the volume of the tunnel, for example, due to swelling (rheumatoid arthritis), trauma (distal radius fracture and haematoma) or mass lesion (lipoma or ganglion) will compress the nerve, leading to symptoms, although the majority of carpal tunnel syndrome cases are idiopathic.

Patients complain of intermittent numbness with pins and needles affecting the thumb, index, middle and radial half of the ring finger. There may be associated weakness and wasting of the thenar eminence muscles. Physical tests include Phalen’s test (holding wrist in flexion for 60 seconds to bring on symptoms) and Tinel’s test (tapping over carpal tunnel to exacerbate symptoms) and may be reinforced with nerve conduction testing.

Treatment may be attempted with splints or steroid injections but, with continued symptoms or if there is evidence of nerve denervation (thenar wasting or weakness), surgical decompression should be offered. This is performed under local anaesthetic, which allows complete division of the transverse carpal ligament, relieving the nerve compression. Symptoms may not improve but should not worsen and it may take months

for some recovery to be seen. Risks include recurrence, nerve damage and scar sensitivity.

Median nerve compression in the carpal tunnel is the most common entrapment neuropathy in the upper limb, causing pain and numbness in the distribution of the nerve. The carpal tunnel has 3 sides which are rigid bony structures, its floor being the proximal carpal row, with the side walls of the scaphoid and trapezium radially and the pisiform and hook of hamate ulnarly. The roof is made of the transverse carpal ligament, another rigid

structure. Through this tunnel runs the median nerve, accompanied by 9 flexor tendons. Any change in the volume of the tunnel, for example, due to swelling (rheumatoid arthritis), trauma (distal radius fracture and haematoma) or mass lesion (lipoma or ganglion) will compress the nerve, leading to symptoms, although the majority of carpal tunnel syndrome cases are idiopathic.

Patients complain of intermittent numbness with pins and needles affecting the thumb, index, middle and radial half of the ring finger. There may be associated weakness and wasting of the thenar eminence muscles. Physical tests include Phalen’s test (holding wrist in flexion for 60 seconds to bring on symptoms) and Tinel’s test (tapping over carpal tunnel to exacerbate symptoms) and may be reinforced with nerve conduction testing.

Treatment may be attempted with splints or steroid injections but, with continued symptoms or if there is evidence of nerve denervation (thenar wasting or weakness), surgical decompression should be offered. This is performed under local anaesthetic, which allows complete division of the transverse carpal ligament, relieving the nerve compression. Symptoms may not improve but should not worsen and it may take months

for some recovery to be seen. Risks include recurrence, nerve damage and scar sensitivity.

Lower limb problems

Knee meniscal tear

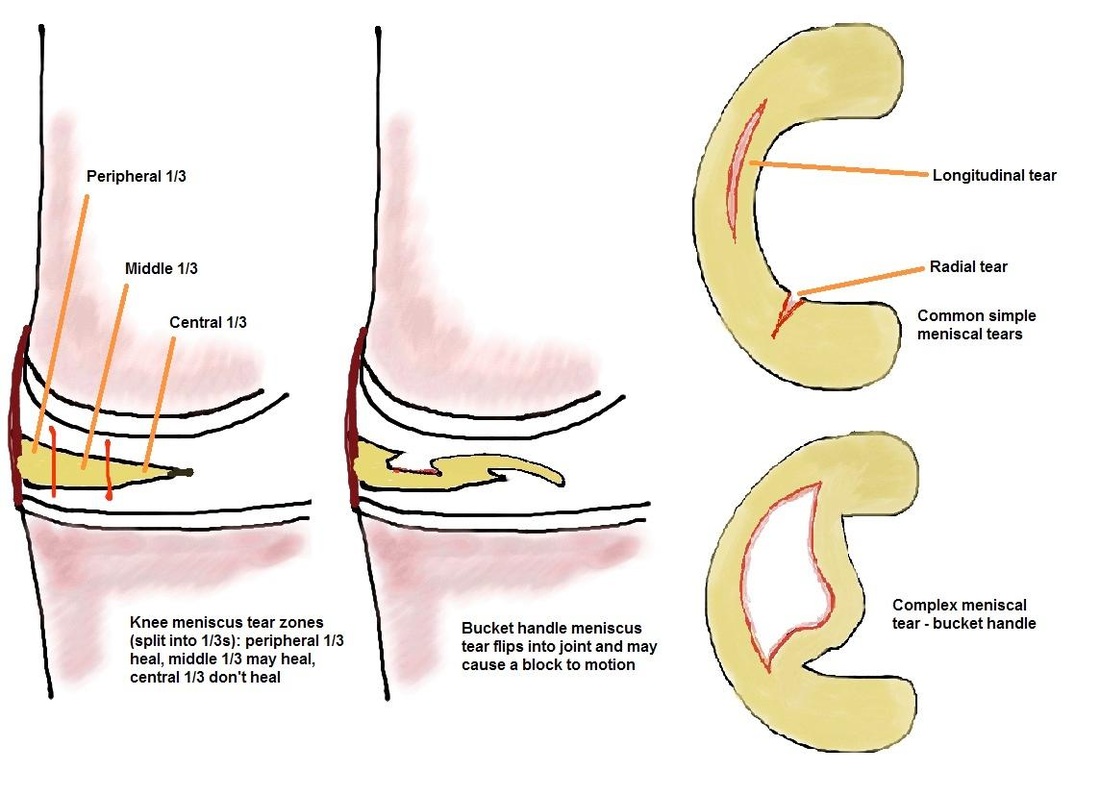

Menisci are C-shaped medial and lateral cartilages that play an important role in knee mechanics, providing load-transmission, joint lubrication, stability and possibly proprioceptive function to the knee. Damage may occur in a young sports person during a twisting injury, often associated with an ACL tear, or may be seen in older patients as a result of degeneration of the biomechanical structure of the meniscus. Tears may be

simple radial or longitudinal tears or more complex “bucket-handle” tears with a portion of the damaged meniscus flipping into the joint. The peripheral 1/3 of the meniscus is vascular and tears involving this region have a chance of healing whilst the central 2/3 are unlikely to heal due to avascularity.

Knee meniscal tear

Menisci are C-shaped medial and lateral cartilages that play an important role in knee mechanics, providing load-transmission, joint lubrication, stability and possibly proprioceptive function to the knee. Damage may occur in a young sports person during a twisting injury, often associated with an ACL tear, or may be seen in older patients as a result of degeneration of the biomechanical structure of the meniscus. Tears may be

simple radial or longitudinal tears or more complex “bucket-handle” tears with a portion of the damaged meniscus flipping into the joint. The peripheral 1/3 of the meniscus is vascular and tears involving this region have a chance of healing whilst the central 2/3 are unlikely to heal due to avascularity.

A patient with an acute meniscal tear will describe a twisting injury with sudden onset of pain on either the medial or lateral side of the joint with swelling developing over 12-24 hours. The patient will present with pain and a limited range of motion and an effusion. Investigate initially with X-rays to rule out a fracture but continued symptoms are investigated with MRI. MRI will show the extent of the tear and associated ligament disruption or bony injury.

Treatment may be conservative if the pain settles and the patient can achieve a full range of motion (particularly full extension) once the effusion has resolved. If there is evidence of a peripheral (repairable) tear or there is a block to full extension (due to a flipped bucket handle tear), a knee arthroscopy with meniscal repair (via sutures) or partial excision may be performed. Symptomatic degenerate, chronic meniscal tears (usually seen in patients over 40 years of age), often involving the posterior horn of the medial meniscus, may be treated with arthroscopic meniscal debridement. Total excision of a meniscus leads to early development of osteoarthritis and is never performed.

Treatment may be conservative if the pain settles and the patient can achieve a full range of motion (particularly full extension) once the effusion has resolved. If there is evidence of a peripheral (repairable) tear or there is a block to full extension (due to a flipped bucket handle tear), a knee arthroscopy with meniscal repair (via sutures) or partial excision may be performed. Symptomatic degenerate, chronic meniscal tears (usually seen in patients over 40 years of age), often involving the posterior horn of the medial meniscus, may be treated with arthroscopic meniscal debridement. Total excision of a meniscus leads to early development of osteoarthritis and is never performed.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injury

The ACL is an important stabilising structure of the knee, providing anterior translational and rotational stability. Rupture occurs in sportsmen with a non-contact twisting injury resulting in sudden pain and immediate large swelling/haemarthrosis.

Examination will reveal positive anterior drawer and Lachman’s tests. MRI will show the extent of associated meniscal and bony injuries and confirm ACL rupture. Treatment commences with achieving full range of motion in the knee. Any attempt at surgery prior to this may result in arthrofibrosis with severe chronic stiffness and limited motion of the knee. Having achieved full motion, the patient will commence ACL rehabilitation under the

guidance of physiotherapists, working on quadriceps strengthening and hamstring control. If the patient suffers knee instability despite this rehabilitation, ACL reconstruction surgery may be considered.

ACL reconstruction is classically performed arthroscopically and may utilise tendons harvested from the patient’s hamstrings or part of their patellar tendon. Tunnels are drilled in the tibia and femur at the sites of the native ACL attachments and the tendon graft secured at these points to form a substitute cruciate ligament. Prolonged rehabilitation is required following this surgery to allow return to sport.

The ACL is an important stabilising structure of the knee, providing anterior translational and rotational stability. Rupture occurs in sportsmen with a non-contact twisting injury resulting in sudden pain and immediate large swelling/haemarthrosis.

Examination will reveal positive anterior drawer and Lachman’s tests. MRI will show the extent of associated meniscal and bony injuries and confirm ACL rupture. Treatment commences with achieving full range of motion in the knee. Any attempt at surgery prior to this may result in arthrofibrosis with severe chronic stiffness and limited motion of the knee. Having achieved full motion, the patient will commence ACL rehabilitation under the

guidance of physiotherapists, working on quadriceps strengthening and hamstring control. If the patient suffers knee instability despite this rehabilitation, ACL reconstruction surgery may be considered.

ACL reconstruction is classically performed arthroscopically and may utilise tendons harvested from the patient’s hamstrings or part of their patellar tendon. Tunnels are drilled in the tibia and femur at the sites of the native ACL attachments and the tendon graft secured at these points to form a substitute cruciate ligament. Prolonged rehabilitation is required following this surgery to allow return to sport.

Hallux Valgus/Bunions

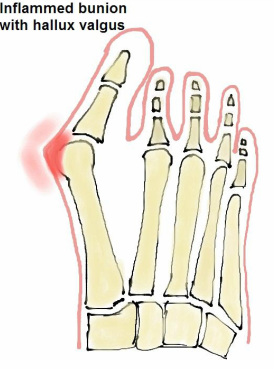

Varus deviation of the hallux (big toe) metatarsal will lead to a valgus angulation at the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ), termed hallux valgus. This angulation will result in a prominent bump (inflamed capsule, bursal tissue and joint osteophytes) on the medial side of the joint, which is referred to as a bunion, and may cause pain and rubbing on shoewear. After investigation with X-rays, treatment is decided on according to the patient’s symptoms.

Varus deviation of the hallux (big toe) metatarsal will lead to a valgus angulation at the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ), termed hallux valgus. This angulation will result in a prominent bump (inflamed capsule, bursal tissue and joint osteophytes) on the medial side of the joint, which is referred to as a bunion, and may cause pain and rubbing on shoewear. After investigation with X-rays, treatment is decided on according to the patient’s symptoms.

|

Hallux valgus may be treated non-operatively with accommodative wide shoes and avoiding tight shoes. Surgery corrects the underlying deformity of the great toe to alleviate symptoms and should never be performed for cosmetic reasons alone. There are many described procedures that involve correcting soft tissue balance around the MTPJ and excising the bunion in minor deformity. Correction of greater deformity involves cutting and realigning the metatarsal and sometimes the proximal phalanx, combined with soft tissue procedures. All of these procedures have a risk of recurrence of deformity and hallux valgus may eventually lead to MTPJ osteoarthritis, which if symptomatic, can be treated with fusion of the joint in the corrected position. |